http://www.conwex.info

|

Dr. med. vet. Christiane Haupt:

Veterinary Help for Common Swifts

How can I tell that the Swift I have found is in bad shape?

A bird that has had an accident in shock: ruffled feathers, closed eyes. Photo: C. Haupt

Possible symptoms:

No Common Swift will be found on the ground without a reason! Never just throw the bird up into the air! A thorough examination of the foundling, is necessary to find out exactly why the animal was grounded and in order to give sensible and purposeful help.

Broken bones and torn ligaments a) Wings If your foundling has a broken or dislocated wing, the prognosis is poor. Swifts are high-performance flyers and healthy flying equipment is vital. During the course of their life, which can last more than 20 years, they fly approx. 200,000 km per year. Always remember, that a Swift cannot make any compromises: it must either be able to fly in perfect condition – or will die in a pitiful state.

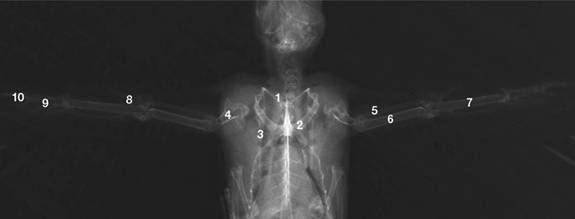

However, don’t despair too soon, if a wing is hanging down: there are favourable cases, which can be treated. A vet, who is knowledgeable about birds, will take an x-ray and assess the situation.

Conservative fixation with figure-eight-bandage. Photo: C. Haupt

Scalped wound inflicted by a cat: hopeless. Photo: C. Haupt

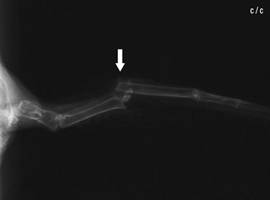

Patient after the operation: Internal fixation of a broken radius with an intramedullary pin (IM pin, arrow: nail exit). Photo: C. Haupt

b) Shoulder girdle

Asymmetric position of wings with a dislocated shoulder: This Swift will never fly again and must be put down. Photo: I. Polaschek

The most important bones in the bird’s shoulder girdle are the filigree silver-fork bone and the strong coracoid bone. If a Swift hits an obstacle at high speed, these sort of fractures and torn ligaments occur quite often – and they are always hopeless. Externally you can not see more than that the Swift is unable to fly or only a short distance. Because these fatal injuries are not so obvious as e.g. a broken wing, one can hardly believe that the bird cannot be saved.

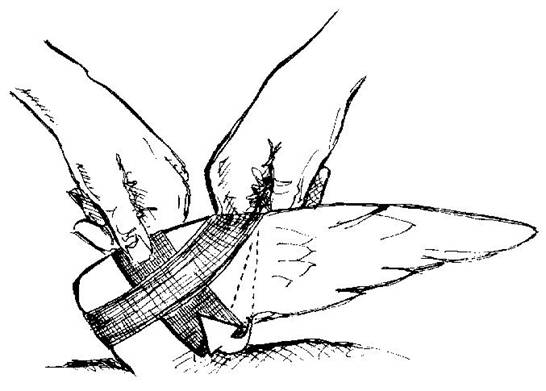

Internal fixation with IM pins of ulna and radius. Drawing C. Haupt

c) Leg Young Common Swifts often break their legs when they fall from their nests or when the Swift gets caught in a thread at its nesting site and tries in vain to break free. Unfortunately, it happens now and again that such a bird hangs helplessly on the roof under its nesting site, and without attentive neighbours and a willing fire service is sentenced to an agonizing death that can last for days. But if its lucky enough to be saved, you’ll often be dealing with an extremely swollen, twisted or even numb foot. As a rule, a broken leg heals without any complications if it is immobilised with a small bandage around its body, and a slightly crooked positioning does not impair the bird. If you are dealing with a complicated leg fracture, a foot, which is only hanging on by tendons and skin or with a dead limb, the vet should amputate. It has been proven that Swifts can live without any problems with one leg only and can even breed. d) Beak Fractures of the lower beak almost always occur through feeding, which is not careful enough or too rough: frequently the fingernail is only placed at the tip of the beak and the beak is bent downwards, which almost always breaks the fine bone. This fracture is unnecessary and avoidable and may lead to severe deformations! Often the upper and lower beak do not fit properly over each other; uncontrolled horn growth may be the result. In the worst case it leads to a loss of parts of the beak’s horn sheath or even to the tip of the beak breaking off – a death sentence! A broken beak requires the utmost gentleness and care during feeding. A fixation by the vet as soon as possible is advisable.

Fixation of a lower jaw fracture with a bit of quill: C. Haupt

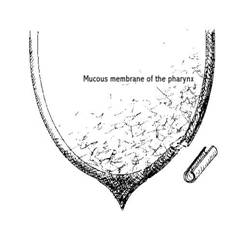

Advice for the vet

To fixate an uncomplicated mandibular fracture, a small piece of quill can be used as a splint, e.g. from a pigeon feather, which is cut open lengthways, pushed over the broken part like a slide, if required and then left for a few days. The stability achieved in this way is satisfactory. There were no irritations of the mucous membrane of the pharynx in the area of the splint for the cases under observation, but this should be closely monitored.

Advice for the vet

Due to the way of life and high specialisation of this kind of, it should be clarified in advance, whether and - if yes, how – the damage to its flying system can be repaired and at the same time its ability to be reintroduced into the wild can be ensured. The following experiences have so far been listed:

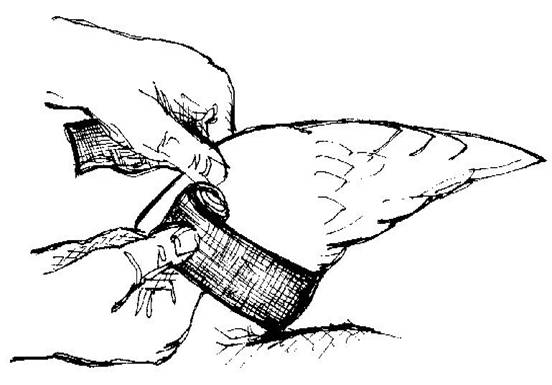

A conservative fixation should only be carried out on one side and material be used, which does definitely not damage the feathers, self-adherent bandages seem the most suitable. An intact plumage is as vital for an aerial flyer as an undamaged skeleton! The figure-eight-bandage has proven its worth (see drawing). After removing the bandage, the bird should be trained for a few days, in order to strengthen its muscles. For this purpose it can be left to climb every day, fluttering his wings, or encouraged to do some exercises on the ground. Letting it fly across the room is not advisable, as a Swift reaches high speeds at even short distances, and could too easily injure itself.

The wing is placed in a physiological position. The pressure-sensitive stretched skin of the wing (arrow) must be carefully padded. Drawing: C. Haupt

An elastic bandage is applied from ventral to dorsal around the humerus, then across the shoulder joint and around the carpus. Drawing: C. Haupt

The bandage is placed dorsally across the wing, pulled as a figure-eight-bandage ventrally again and along under the humerus. Drawing: C. Haupt

As far as possible, the surgical care of the fracture is definitely given the priority where the Swift is concerned. Internal fixation has proven itself to be successful in many cases, can be carried out fast and easily and is least awkward to the patient during convalescence. The plumage must on no account be damaged during the operation. After the IM pin has been removed, it will be necessary to have a few days of physiotherapy.

The relatively frequent radius fracture, which, if not treated, can lead to limited flight ability, is pinned by using a 0.4 mm cannula, which is inserted into the distal end of the fracture, exits through the radius head which is palpable at the shoulder joint and is retrogradely pushed into the proximal end of the fracture as far as just in front of the elbow joint. The pin coming out at the shoulder joint is released 1 - 2 mm over the skin, and is protected with a small adhesive strip, so that the patient is unable to pull it out. The ulna is pinned in the opposite direction; here the pin exits, being bent at a maximum, at the proximal end of the ulna just underneath the elbow joint. A 0.5 mm cannula or drill wire can be used. Caution: the ellbow joint may stiffen! For the radius the medial, for the ulna the dorsal access has proven successful.

A defect in the shoulder girdle can be diagnosed by the bird’s inability to fly or only in a restricted way, an incongruent movement of wings, or the shoulder concerned hanging down, as well as the inability of the Swift to turn round on its own accord when you try and put it on its back. An x-ray is essential in order to exclude the possibility of bruising. An exact positioning is indispensable for an impeccable picture of the shoulder girdle area. If necessary, sedating the patient may be advisable. The shoulder girdle defects occurring most frequently are fractures of the clavicula and the coracoid as well as the luxatio articulatio humeri (shoulder luxation), which clinically shows itself in the same way and can be clearly diagnosed in the x-ray: the very often significant dislocation of the upper arm as well as the clearly enlarged distance between the humerus head and shoulder joint of the side concerned are visible. It is harder to diagnose luxatio art. sternocoracoidea, which is not so infrequent: the sinewy attachment of the coracoid to the breastbone is torn off with a dislocation beyond the median. This defect can easily be overlooked on the x-ray and requires a trained eye.

Bruising Bruising, especially of the shoulder occurs frequently among Swifts, and manifests itself clinically in a similar way to a fracture or torn ligament in the shoulder girdle, although the shoulder looks symmetrical. If the Common Swift does not stretch a wing, but protects it or presses it tightly to its body, it is essential to take an x-ray. Because bruising, although extremely painful, can be healed! Usually the swift already starts to carefully move the wing after a few days. Afterwards, a continuous improvement can be observed, and at the end of approx. 10 to 14 days you can carefully begin physiotherapy. Experience shows that at the end of three to four weeks the bird has completely regained its ability to fly.

Antibiotics a) Cephalosporine (Cefotaxim p.e., “Claforan 0,5”) 100 mg/kg body weight i.m. or s.c. SID-BID 5-7 d. Good when the bird has been bitten by cat. b) Enrofloxacin („Baytril“ 0.5 % oral solution) 10 mg/kg body weight p.o. BID 5-10 days; for Staph. and E. coli partially resistant, therefore, if required, combination with c) Amoxicillin/Clavulanacid („Augmentan-drops“) 150 mg/kg bodyweight p.o. SID over 5-10 days

Never give any antibiotics without giving simultaneously prophylactic antimycotics (Itrakonazol)!

Injuries If the wounds have been inflicted by a cat, it must be given an antibiotic as soon as possible, and every hour counts: in general, untreated cat bites result in death within a very short time. Through the cat’s saliva pasteurella, can be transmitted into the bird’s bloodstream, causing its death from sepsis.

Eye injuries usually have a bad prognosis. Please give analgesic drugs immediately, Meloxicam p.e. Under extreme swelling, bloody crusts etc. there is unfortunately usually an eye that has been destroyed. A Common Swift cannot live with one eye only, as it then lacks its spatial sight and is unable to catch food. Bleeding from the nose or beak often occur after the bird has flown against something; in this case emergency treatment by the vet is required. Bleeding from the ear is typical for a basal skull fracture; there is nothing left but euthanasia.

Medication: Amynin / Ringer-Lactat 1:1, 1 ml body warm s.c. (wrinkle of the knee) Naphthionacid ("Hemoscon") 100 mg/kg i.m. Traumeel injection solution drop by drop p.o. (also after an operation, after hitting an obstacle, against bruising; 1 drop BID - TID)

Meloxicam ("Metacam-Suspension") 1 drop BID a couple of days

Sedation: Diazepam (4-6 mg/kg KGW i.m.)

Anaesthetic: Inhalation narcosis Isofluran (introduction 3-4 min. 2.5-5% Isofluran + 1-2 l/min. O2, maintenance 0.5-2 % Isofluran + 0.5-1 l/Min. O2) or Injection narcosis with Diazepam (4-6 mg/kg body weight) and Ketaminhydrochloride (60 mg/kg body weight) i.m. in two different injections (both in one injection will cause muscle necrosis); if required, administer further with Ketamin (40-50 mg/kg bodyweight). With excitation administer further with Diazepam (5 mg/kg KGW).

In painful treatment, always give analgesics!

Euthanasia: (Before euthanasia give an anaesthetic first!) Ketaminhydrochloride („Hostaket“, „Ketanest“) 250 mg/kg KGW s.c., then 0.05 – 0.1 ml "T 61" i.v. or i.c.

Damage to large feathers Repeatedly Common Swifts are found by humans as a result of damage to their feathers, probably caused by accidents: with snapped, broken off feathers or feathers missing for unknown reasons. Such damage is usually only limited to one wing (in contrast to feather defects which are the result of a genetic fault or a wrong diet, which usually occur symmetrically).

Tragically, this also happens: a young Common Swift, whose primary feathers were maliciously cut off from both wings. He was saved through imping! Photo: C. Haupt

The decision, what to do with such a poor bird, is not easy. It is possible to carefully pull the damaged primary feathers under general anaesthesia. However, the quills of the large hand primary feathers are anchored extemely tight – up to the forearm bone! -, and there is a great risk, even if removed by an expert, of causing severe injury. Often new feathers do not re-grow or are deformed. Even in the most favourable case, it will be seven to eight weeks before the new primary feathers have completely grown back. The method used in falconry of imping, i.e. placing undamaged feathers onto the quills of the damaged ones, can come to the rescue of such cases of birds, but it is not a routine operation for Common Swifts.

Dehydration and Malnutrition

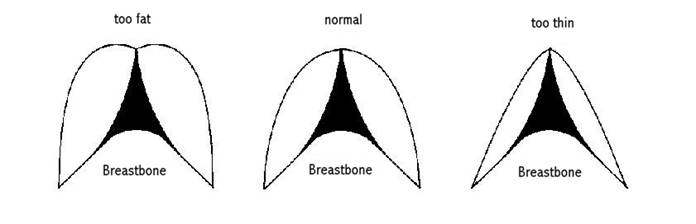

Examine the animal’s breast: if the bone (breastbone) projects sharply, almost like the keel of a ship, the bird has become extremely thin. In that case, drip a few drops of a glucose solution (10 g glucose in 100 ml lukewarm water) with a pipette or plastic syringe (of course, without the needle) every 15-20 minutes into the beak, without smearing the bird with the sticky solution. The bird must not be lying on its back, it could choke and suffocate.

It is essential that the bird is kept warm (approx. 32°-35° C).The most suitable is warmth from below.

If the Swift has become extremely thin, there is a risk that it will not even take liquids, let alone solid food. The circulation of such a bird is usually seriously malfunctioning, as is its digestion. As a rule, this applies to young Swifts, which only weigh just above 20 g or even less. They are acute emergencies. According to the latest experience, many of these starving birds can be saved through a vet’s infusion, which should be repeated after 12 hours. (Amynin / Ringer-Lactat 1:1; 1 ml body warm s.c.)

These strengthening remedies will get the circulation going again, you gain time, in order to carefully start feeding the bird. The preparation „Pancreaon“, which supports the digestive system, can be obtained from chemist stores and has proven itself in such cases: 3-4 times per day you mash 1-2 small balls, dab the powder with a bit of food and adminster it to the patient until the bird’s condition is stable and it gains sufficient weight.

When the Common Swift starts improving, you feed it a few small crickets approx. every half hour – preferably at first only the soft back parts – (or if you have them, the somewhat firmer yellowish drones), and watch, whether the bird produces excrement. This is extremely important! Although severely undernourished, young Swifts often devour the food ravenously, and would like to swallow their carer’s whole finger, they are much too weak to digest the food. When a Swift is desperately begging you for food, temptation is great to give it as much as it wants. However, after a first improvement, this rapidly leads to a critical overloading of the bird’s stomach, often resulting in death. Weight increases of several grammes in only a few hours are warning signs!

Regularly check by carefully feeling with your fingers, whether the bird’s body is well filled, yet is soft and yielding! A hard stomach, which bulges as round as a ball means maximum alert (in this case, immediately stop feeding, and preferably have the vet give the bird another infusion with stengthening remedies). It can take several days to stabilise a young Common Swift who has lost so much weight. During this time, the stomach may feel hard from time to time, even if you feed very carefully, but if you strictly keep to giving the bird small and easy to digest food quantities at short intervals, the above-described emergency situation should not happen. Until the patient is really on the mend, the breaks between feeding during the night should not be longer than 4-5 hours. After that you can start to feed normally, and get some well-deserved regular hours of sleep.

Flying against obstacles Many birds that hit power lines, cars, windows or similar are dead on the spot, so that they cannot be helped. However, if the bird survives the impact, it is necesssary to act quickly: the vet has to treat the bird against shock as soon as possible.

"Convulsions" Cramps and disfunctions of the central nervous system can have very different causes. Frequently they occur as a result of an accident, and sometimes the Swift gets away with a concussion, is simply weak and dazed, but recovers after a few days of rest and warmth. But if more serious symptoms occur, such as convulsive seizures, spinning movements, rolling over, stereotype head movements, the prognosis is doubtful. Such patients should be taken to a vet with a good knowledge of birds, as quickly as possible!

Convulsive seizures as a result of a lack of vitamin B. Photo: C. Haupt

Frequently observed convulsive fits, which can happen very sudden, rapidly progress and, if left untreated, can lead to death, develop as a result of a lack of B-complex vitamins. This, in particular, affects Swifts, who are fed with meal-worms or crickets of inferior quality, as well as those, who have to stay with humans beyond the time of their normal rearing.

The symptoms start imperceptibly with a reluctance to eat, a fixed stare and compulsive head movements and intensify to throwing-its-head-right back, and to uncontrolled convulsions and spinning movements. The vet can immediately treat such a fit with an injection of Vitamin B-complex. Administering vitamin B into the beak has been mostly ineffective when treating Common Swifts. Preventive feeding does not always avert these deficiency symptoms, either.

Parasites Often Common Swifts are stricken by featherlings, mites and especially the bloodsucking Swift louse fly (crataerina pallida). These so-called ectoparasites sometimes appear in such large numbers that they can become life-threathening to a weakened young Swift. The Swift louse fly is not unsimilar to a housefly, but it has atrophied wings and has suction feet, with which it also attaches itself to human skin. It likes to jump onto humans and owing to its hard shell can hardly be squashed with our fingers. A Common Swift’s ectoparasites are not dangerous to humans, unpleasant at the most. You can sprinkle a tiny amount of insect powder, which is suitable for birds, (e.g. „Bolfo Powder“) and which you will get in any specialist pet shop, on the bird’s neck feathers and distribute it.

Swift louse fly, approx. as big as a housefly. Photo: U.Tigges

Common Swifts quite often have endoparasites. There have been several proven cases of tapeworm, which live as a parasite in the Swift’s intestines, and, under specific circumstances, can lead to the death of the bird. You can even recognise such worms in the excrements with the naked eye; they are tiny and move. Hairworms are rarer; its eggs, too, can be detected when the excrements are examined.

Cestodes and nematodes have been detected in Common Swifts. Especially old birds are often affected. Experience shows that exremely thin Swifts are suspected of having tapeworms, which after one or two days of continuous initial improvement in their condition, no longer gain weight, suddenly reject their food and show a rapid deterioration in their general state of health. Immediately administering Praziquantel („Droncit“ 10 mg/kg bodyweight p.o. or 5–10 mg/kg bodyweight i.m., repeat after ten days) has helped in many cases. During flotation tapeworms are not detected, and sedimentation does not always say much either! Due to the extremely progressive clinical picture of the cestodes infestation a prophylactic therapy might be advisable, if necessary. Occasionally, Swifts that were wrongly fed with earthworms for a short while, were subsequently affected by windpipe worms. Dyspnoe and breathing noises are clinical symptoms for such an infestation. Fenbendazol („Panacur-suspension 2.5 %“, 25 mg/kg bodyweight p.o. SID 3 days, repeat after 10 days) has proven itself effective against syngamus, ascarides and capillaries.

Diseases Only little is known about infectuous diseases among Common Swifts. Non-specific evidence would be e.g. apathy, difficulty in breathing, paralysis, ruffled feathers, bent up back, conspicuouly pale, yellowish or bluish mucous membranes, stratifications in the throat, smeared plumage under the tail, foul-smelling excrements.....

The diseases of Common Swifts, which have so far been observed by the writer could almost exclusively be traced back to mistakes made by people whilst keeping and feeding the bird, and manifested themselves as severe dyspepsia, and damage to liver, kidneys, skeleton and plumage.

A lack of hygiene during feeding can also lead to a number of very persistent bacterial infections and mycoses. They can be made more difficult through the wrong diet, deficiencies and a weakened immune system, and usually manifest themselves in the area of the throat and in the respiratory tract. Clinically dominant are changes in the throat (whitish or brownish spots, coating or crusts, mucous threads, sweet smell etc.), breathing noises or difficulty in breathing. The throat area of Common Swifts, which have never been cared for by humans, is usually sterile. „Pre-treated“ Swifts, however, often show a wide spectrum of germs which are facultatively pathogenic, among others pseudomonas spp., proteus, E coli, Klebsiella, ß-haemolysing streptococcus, staphylococcus aureus. Frequently these germs appear together with candida albicans. The Swift’s candidiose responds well to Flukonazol, although this has a hepatotoxic effect, so that treatment with Nystatin (works locally, must have contact with the yeast) is a preference.

There is a strong proneness to an aspergillosis of the respiratory tract when treated with antibiotics, as well as with a weakened immune system. If the infection has not progressed too far, therapy with Ketokonazol is possible.

The bacterial and mycological examination of a throat swab as well as an antibiotic spectrum are essential for successful treatment, as a resistance against common antibiotics can be increasingly observed among wild birds.

Antimycotics: • Nystatin (e.g. „Candio Hermal“) 3 ml/kg bodyweight p.o. BID-TID over 10 days (the best against Candida) • Itrakonazol (e.g. “Itrafungol”, “Sempera”) 10 mg/kg bodyweight p.o. SID over 10-14 days (the best against Aspergillus)

First Aid The same basic rules apply to a bird that has an accident as to a mammal: secure vital functions – stop bleeding – treat for shock!

For Common Swifts with commotio cerebri after hitting an obstacle, the following, already described on page 3, has proven itself effective: immediately administer a lactated Ringer’s solution subcutaneously to a volume substitution, as well as corticosteroids i.m., antibiotics and a vitamin-B-complex s.c. Medicine to stimulate circulation and breathing can be helpful. The patient needs strict rest and warmth. The prognosis when birds have flown into an obstacle should always be cautiously made. Internal injuries such as cerebral haemorrhage, skull fractures, spinal injuries and similar injuries mostly lead to death or result in paralysis (e.g. limp legs, completely paralysed claws, lack of excrements) and severe central nervous malfunctions, which in the end require euthanasia.

Circulation and breathing stimulation: • g-Strophantin p.o. a drop at a time after effect. Cave cardiac hypertrophy when given overdosage, esp. in small birds. • Etilefrin „Effortil“ 0.2-1 mg/kg body weight i.m. or a drop at a time p.o. • Dimethylbutyramid „Respirot“ p.o. a drop at a time after effect. Peripheral breathing stimulant. • Doxapram „Dopram V“ 10 mg/kg body weight i.m. or a drop at a time p.o. central breathing stimulant

Damage caused by the wrong diet The experience gained by looking after Swifts have lead to alarming new findings. Especially dietary mistakes and their fatal consequences take first place here. Whilst insect-eating songbirds (e.g. swallows, redstarts, robins, warblers, wrens...) die very soon when given the wrong food, a Swift will react, as a rule, with damages that are delayed yet have the same bad consequences. Liver damage and then plumage defects, which are frequently observed, seem to be the prime consequences for Swifts on the wrong diet. Defect primary feathers, however, are a death sentence for an aerial bird. Usually young Common Swifts very soon start losing their primary feathers or show damage to the quills, even if they have only been given the wrong food for a short time. They also frequently get diarrhoea, very poor digestion, as well as deformations of the skeleton.

Disastrously, a lot of animal food, which has meanwhile proven to be extremely harmful, has been common in feeding young wild birds, and is still being recommended by many experts. We can only hope that many „traditional errors“ are soon replaced by a feeding method, which is orientated towards nature and therefore suitable for the species. That is the only way we can begin to do justice to the various demands on food that feathered foundlings of different kinds of species have and for which there is no „universal recipe“.

So which kind of animal food should we steer clear of and what kind of damage does it do?

Minced meat The probably oldest and most widely spread incorrect information is to feed Common Swifts with minced meat. Anybody who really thinks about it, who knows something about the way of life and feeding habits of a Swift or only watches these birds in the wild, should come to the conclusion that they most certainly do not catch pigs or cows in order to eat them. Their organism is not equipped for eating meat, and certainly not pure or even seasoned meat. It is incomprehensible why this feeding advice, which is not logical at all, has managed to persist all this time. Perhaps, because it is so easy for the carer. A further reason may be that the fatal consequences usually show themselves somewhat delayed. The loss of primary feathers, which occurred in almost all Swifts that had only been fed with minced meat, does not happen before 8-10 days after switching over to insects. That would be the time, when the young Swift, having gained its strength to fly, would already be up in the air. In many cases it never gets that far, because further consequences of feeding minced meat are a lack of calcium in the skeleton and deformed bones, extremely poor digestion, diarrhoea, enlargement of the liver and other deficiencies.

The feather malfunctions range from loss of single feathers, various defects of the vanes (vexillum), calamus and dull, frayed feathers to decreased growth and total loss of the large primary feathers. The tail feathers usually show structural damage and are inadequately developed.

Extreme damage to plumage after feeding a mixture of minced meat and „rearing food“ for a fortnight. Photo: C. Haupt

As already mentioned above, there seems to be no detectable damage when meat is used as a very small part, merely serving the purpose of improving the bonding capacity, of a food mixture otherwise consisting of high quality insect food.

Below: two young Common Swifts, who have lost almost all their primary feathers after being fed meat. Photo: C. Haupt

Mealworms Still a preferred kind of food for birds feeding on insects are „mealworms“, a term for the larvae of the meal beetle (tenebrio molitor), which you can buy in any pet shop.

But I must warn you not to feed these worms in large numbers and over an extended period (longer than 2-3 days). They seem to contain substances in their chitin shell, which in the long run caues severe liver and kidney intoxications. Feeding mealworms is also much too unbalanced and leads to deficiences and skeleton damage. Especially frequent is an undersupply with the vitamin B-complex. This has an effect on the central nervous system, which imperceptibly starts with food rejection and compulsive movements, intensify within the shortest time to serious catalepsies (tumbling over, twisting head, spinning movements), and, if untreated, lead to nerve damage, which cannot be reversed, and ultimately to death. There is also almost always plumage damage, probably also secondary through liver damage. Mostly the calamus sticks to the quills, and when removed the vane underneath is not properly developed.

Damage to the vane and calamus after feeding with mealworms. Photo: C. Haupt

When fed exclusively on mealworms songbirds were also found to develop persistant eye infections which could lead to loss of sight as well as ulcers in the head area, inflammatory swellings of their feet, especially the joints, and abscesses. Mealworms – but only the delicate white ones, which have just shed their skin – may be given as an addition in very small numbers (i.e. not more than 4-5 per day) to insect-eating birds, or as emergency food for a short time, for two or three days, if you cannot get hold of crickets straight away.

Maggots Fly maggots, available as „pinkies“ in angling shops, are completely unsuitable as food for insect-eaters. Owing to their solid rubber-like covering, the bird’s stomach is unable to break them down, so that they are mostly excreted undigested. Even if you prick them before feeding them to the bird, they are not acceptable, as their proportion of fat is very high and they constitute a highly unbalanced diet. Swifts that were fed with maggots, are mostly extremely thin and develop deficiencies as well as fateful defects in their plumage. These are frequently small, hardly visible brittle parts in the quills, where the primary feather then breaks under the slightest strain.

Snapped off feathers after the bird was fed with maggots for two weeks. Photo: C. Haupt

Bird food

Result of rearing the bird with bird food. Photo: C. Haupt

Food mixtures that contain insects, are offered under various names, but if you study the ingredients of such mixtures, you will inevitably find bakery products, which are unsuitable for the digestive system of sensitive insect-eaters. When „grease food“ was mixed with water and fed, we repeatedly noticed breaks in all large primary feathers. Such Swifts were not able to fly. Only pure insect pellets (preferably from „aleckwa“, or perhaps also „Claus“ – type IV blue) should be used.

Earthworms Young Common Swifts are quite often fed on earthworms. But earthworms are not among the range of prey the Swift hunts for in the air and will soon cause extremely poor digestion. It is even worse, however, that they are host to certain parasites. Even through one earthworm a Swift can be infected with the eggs of windpipe worms and become ill a few days later.

Tinned cat or dog food Common Swifts that are fed on cat or dog food, are usually totally smeared, sticky and encrusted, smell miserably and suffer from extremely poor digestion. Afterwards their plumage remains tangled and dull and therefore does not have enough insulating property. The unidentifiable ingredients of tinned cat and dog food are definitely not suitable for the digestive system of insect-eaters and can damage it to such an extent that the birds die or must be put down. I must therefore definitely advise against feeding this sort of food, which is often used in animal shelters.

Young Common Swift having suffered a painful death after having been fed with canary seed for five weeks. Photo: C. Haupt

Other food There is nothing that hasn’t been fed to hungry young Swifts in good faith, but always with the worst consequences: whether budgy or canary seeds, rusk, oats or bread, fruit or sausages, spaghetti, porridge, salami or fried steak – it has all happened and hardly any of the poor things have survived. I could go on talking about unsuitable food for Swifts, but to make it short: only insect food should go down their beaks!

Damage caused by the wrong surroundings The best and most suitable food is in vain if the Swift ruins his plumage for other reasons. This is regularly the case when this special bird is kept in a birdcage. Of course it seems plausible to think of a birdcage when you suddenly have to accommodate a little bird. Unfortunately, that has fatal consequences for a Swift. It will always hurt its primary feathers and its tail on the bars, so that it is no longer able to fly later on. Therefore never keep a Swift „behind bars“ or in any other container with rough walls, which may damage its feathers!

Other mistakes made when keeping Common Swifts The feathers can also be badly damaged, sometimes irreparably, if the container for the Swift is too small or tight or is not kept impeccably clean. Bent and snapped primary and tail feathers, crusted feathers smeared with excrements, bald patches and bruises should and must not occur!

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Photos: C. Haupt Left: young Common Swift with severe plumage damage that has received the wrong food and is smeared with excrements and porridge. Right: bird of the same age reared on crickets.

Lack of hygiene Caring for a Common Swift requires the greatest possible hygiene. Always wash your hands thoroughly before feeding, especially if you are feeding with your finger only and not with tweezers. Feeding utensils (plate, tweezers, syringe...) must be cleaned after each meal with hot water. Always provide fresh drinking water for the bird. Defrosted crickets should be rinsed with lukewarm water before feeding; if you are preparing a food mixture, always make sure everything is hygienic and fresh. Food which has gone off can kill a Swift. Test by smelling it first!

A lack of hygiene will inevitably lead to infections with bacteria and fungi, which Swifts are very prone to - perhaps they don’t have to deal with germs in their own natural habitat - and which can be transmitted by human contact. Once such an infection has taken hold, it is hard to fight in many cases, and may mean the Common Swift has to stay with humans for a much longer time, as well as many injections (every injection is an injury – even if small – of the main flying muscles!) and medicine. Stress, pain and strains which can easily be avoided by ensuring cleanliness and mindfulness!

© APUSlife No. 3468

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

When you found a young Common Swift and have to rear it, please klick here for advices of handrearing: http://www.commonswift.org/Hand_rearing_Swifts.html

When you have to find out how old the chick is, please klick here: http://www.commonswift.org/nestlings_english.html

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||